Life with Siberian Huskies

The Journey is more important than the destination

Sled Run

Barely enough snow but we gave it a try anyway.

Tales from the Queen

This is another chapter in the annals of Queen Nikki the 1st. A true story that has a lesson or two in husky behavior and training.

The most prized treat and possession of my dogs are marrow bones. They are cheap and sliced up beef bones full of the prized and fat heavy bone marrow. Bone marrow delivers 786 calories per 3.5 ounces. It’s very rich in fat which must be why it taste so good to them.

I keep them frozen and dish them out when I want a few hours of piece and quiet. Cooper and Nikki carry these prized bones to some part of the yard. Then they lay down facing each other from a few yards away to guard them until they begin to thaw.

When that happens, they spend a great deal of time knowing out that precious marrow. It’s not easy, they have to work at it like a Kong toy filled with peanut butter only harder. They also gnaw at the bones and since they are raw I don’t worry if they happen to eat a little of it.

The “Pro” side of this is they keep their teeth in excellent condition. On her yearly check, up the vet was amazed at how white and good the Queen’s teeth looked. The down side is given too much it puts on weight. Currently the Queen is a bit over weight. I’m not about to mention it to her… but I have started tracking her meals and cutting back on the fat.

A little fat is not bad on them in winter time. My dogs spend around 16 hours a day outside running around the property. They would stay out all the time, but I make them come in at night. Mainly because I’m worried someone might try to snatch the Queen and hold her for ransom.

Tonight’s episode of course revolves around a bone. I think it’s the equivalent of gold in our world. Its highly desired, fought over, and hoarded. A true treasure for the 4-legged members of the court.

The dogs came in early this evening and went to sleep right away. Around bed time for me I ran them out for a potty break. Cooper came back in a short while and the Queen wasn’t to be seen. I was reading a book so I let her stay out for another hour or so.

When I was ready to call it a night I yelled out the back door for her. Now, the Queen doesn’t always answer these calls. I mean after all she is a Queen in her mind. At times the demands of her staff are ignored.

After several tries at calling, I resigned myself to having to put on shoes, coat, find the flashlight and go out to retrieve her in my PJ’s. Now I have a gate not 20 feet from the back door that leads to the front yard. But the view is blocked by big bushes. I walk around the bushes and just on the other side of the gate I spy her curled up in a self-dug divot. A perfect little husky swirl, covered in black fur for camouflage.

I walk up to her and tell her it’s time to come in. She ignores me and hopes I’ll go away. This is interrupting my bed time plans and I’m not about to quit that easy. I give her butt a push with my foot which usually works to get her up and moving.

Not this time. She’s dead weight and not moving one bit.

When this happens with either one of them usually reaching down and starting to pick them up with my hands under the chest works. Not this time however and I received a menacing growl. Very seldom has she ever growled at me so I was a bit surprised.

In an instant I made my choice. I could have run to the house and got a toy to try and convince her to get up. I could have just ignored her and let her have her way. Or I could have tried using any of the worthless methods some folks would have you do, so that you don’t hurt the dogs’ feelings.

Instead I just ignored her and picked her up off the ground anyway. Sure, I risked a bite, but it wouldn’t have mattered. Sometimes you have to risk it to stay in control of these strong-willed dogs. I wasn’t mad, I wasn’t mean or rough but I made it known that she was going to get up.

Once on her feet she snatched something from her little hole in the ground. Yes, you guessed it. One of those bones she loves so much. She was guarding it from Cooper or anyone else that might have found it during the night.

I reached for it in her mouth and she gave it up without a growl. She followed me to the back door and in we went. It was all caked with dirt from being buried so I washed it off and gave it back to her. She immediately wanted to take it back outside.

That wasn’t going to happen so I told her I’d put it in the freezer for safe keeping. She watched me do it and was satisfied it was safe. Then she went to her little bed and after 6 twirls curled up and the incident was over.

No pain, no tricks, just a lesson for the Queen that she can’t always have her way.

The morale of this story is that you have to understand your dog(s). A husky depending on its personality can take over if you let them. I really wasn’t too worried about being bitten because we’ve done this once or twice before over different issues.

It started during puppy days, and the Queen has a very strong drive and personality. She learned early that sometimes I was going to win. That lesson stayed with her at some level. She didn’t bite because she believed I was going to take it no matter what.

That doesn’t mean she is going to give up testing me. She’s a husky and one with her own plans about how our pack should be run. Tonight, she got another update in pack hierarchy.

She doesn’t hold it against me. She just went to bed and it’s a done deal until next time she feels the urge to test the boundaries of her world. I let her do husky stuff that really doesn’t matter to me. She can rule the other dogs if she wants but there are limits I impose when needed. Its completely fair and they accept discipline if its handled correctly.

And that means fairly, consistently, and without anger on my part. If your going to lead the pack, that is the correct way to do it. Understand your dogs needs and what drives them. They have simple wants but they are very important to them. So, use your big brain and not your frustrated feelings when the issues show up.

You will have a much better relationship, that both you and your dog will enjoy.

TJ

(If you like articles like this one let me know by clicking the like button at the bottom)

Husky Mobile

In slow motion:

Poland Spring Kennels

My partner Jonathan running the Seppala’s up in Maine.

Living in the moment

Togo – The True Hero

Togo – A Capsule History

Above: Togo, immediately after completion

of the 1925 Nome Serum Run.

Named after Heihachiro Togo, a Japanese Admiral who fought in the war between Russia and Japan (1904-5) as well as other conflicts.

Born: Estimated to be 1913, according to many reliable quotes, including from Leonhard Seppala himself, which place his age at 12 years in 1925, the year of the serum run (exact date not specifically known, or not a matter of public record)

Died: December 5th, 1929

Owner: Norwegian Leonhard Seppala (pronounced LEH-nerd SEP-luh), a breeder and racer of Siberian dogs from the Chukchi Inuit stock of Siberia. He also trained dogs and mushers. Was employed by Norwegian Jafet Lindeberg’s (pronounced YAH-feht LIN-deh-berg) Pioneer Gold Mining Company (Jafet Lindeberg was one of the “Three Lucky Swedes” who discovered gold at Anvil Creek in 1898, near Nome).

Sire (father): Suggen (a half Siberian husky, half Alaskan Malamute, and one of Leonhard Seppala’s other great lead dogs before the days of the serum run).

Above: Togo and some other dogs owned by Leonhard Seppala, prior to

1925. This photo shows the dogs working on one of the claims of the Pioneer Gold

Mining Company, for which Leonhard Seppala worked (before and after the

serum run). This company was later bought out by the Hammon Consolidated

Gold Fields, for which Seppala continued working. At the left of the photo is Togo’s

sire (father), Suggen, who was Seppala’s racing team leader before World War I. He led

Sepp’s team to victory in a few of the All-Alaska Sweepstakes races.

Dam (mother): Dolly (a Siberian husky imported to Alaska, from Siberia, to Leonhard Seppala’s kennels…one of the original group).

Offspring: Togo (II), Kingeak (most likely named after young Eskimo Theodore Kingeak, who assisted Seppala in 1926/7, when he visited the U.S. on tour with 44 of his dogs, including his serum run team, as a dog and equipment handler), Paddy, Bilka (and others).

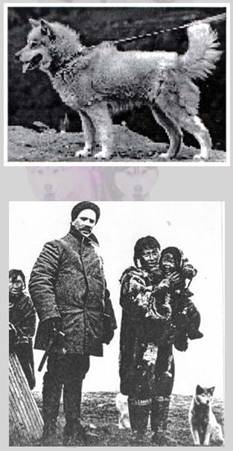

Breed: Dark brown (w/cream, black and gray markings) Siberian husky (of the Chukchi Inuit Siberian tribe’s stock). Eyes were ice blue. He was small for his breed, only topping out at about forty-eight pounds (Seppala liked to referred to Togo, in his racing days, as “fifty pounds of muscle and fighting heart”).

Above: Leonhard Seppala with Togo, after the

serum run.

Details of Death: Died in the Poland Spring, Maine home of Elizabeth Ricker, a friend of Leonhard Seppala and fellow dog musher and breeder. Seppala left Togo, with great sadness, with Ricker to retire in comfort in 1927 (Seppala remembered it as one of the saddest moments in his life. He was quoted as saying “It was sad parting on a cold gray March morning when Togo raised a small paw to my knee as if questioning why he was not going along with me.”) In 1960, in his old age, Seppala recalled “I never had a better dog than Togo. His stamina, loyalty and intelligence could not be improved upon. Togo was the best dog that ever traveled the Alaska trail.”). Togo sired some offspring during that time, and then died of old age in 1929 (Seppala had him “put to sleep” to ease his passing).

Notes:

– Togo was 12 years old in 1925…that’s pretty advanced in age for a sled dog, let alone a lead dog (most of them are retired by that age)! However, it also demonstrates just how much Seppala trusted Togo, and speaks volumes about the amount of experience the dog had.

Above: Togo, taken after the serum run.

– As far as coloration, Togo’s coat was what is known as “agouti” (http://www.huskycolors.com/agouti.html andhttp://www.huskycolors.com/willie.html). His colors were mostly gray, brown, black and creamy white.

– One CLEAR way of identifying Togo out of a line-up of other Siberians (with the same coat pattern) in a photograph (or even assuring that a photo of a dog is or ISN’T Togo) is to look for Togo’s damaged right ear. There is no mention in the historical record of how this happened. It could have been a birth defect, or it’s just as likely (and probably more so) that it is the result of damage from an argument or fight with another dog. Sometimes ear damage just doesn’t heal right. Of course, there is a mention in his history that, while still a puppy, he ventured too close to a trail-hardened team of Alaskan Malamutes, and must have upset one of the dogs, which mauled him. Togo was saved and attended to medically, of course, but that too could have been the cause of this injury.

– Togo’s father was a dog named “Suggen”, a half-Siberian husky/half Alaskan Malamute, whom Seppala had also used as a lead dog (and in whom Seppala had a great deal of faith and trust)…especially during his racing days prior to World War I. Both Suggen and Togo worked on Seppala’s racing teams, and did much to earn him the many trophies in his personal collection.

– Togo, as a puppy, had developed a painful throat disorder which at first caused Seppala to lose interest in him, and even give him up for adoption. But Togo was a persistent puppy, and wouldn’t be parted from Seppala and his teams. After a few short weeks, he escaped from the adoptee’s home by jumping through a window, and meticulously working his way back to Seppala’s home (a good distance away from where he was living at the time). In some pictures, you can see the effects of this if you look at Togo’s neck. The disorder was treated of course, and Togo turned into a remarkable sled dog in spite of it.

– Unlike Balto, whom Seppala had neutered at six months of age, Togo sired many litters of puppies for Sepp’s breeding program, and today is widely considered one of the fathers of the modern Siberian Husky breed (as well as a strong contributor to the much older “Seppala Siberian Sled Dog” breed…the genetic forerunner of the modern Siberian Husky, and the breed which was once called “Siberian husky”).

– Togo also worked for a living, helping Seppala’s freighting teams in his employ with the Pioneer Gold Mining Company.

– Togo and his team ran nearly five times as far, during the Serum Run, as any of the other nineteen teams which participated (a grand total of 261 miles/420 kilometers). Due to changes made after Seppala left Nome with his team, and the inability to get word to him on the trail, Seppala ran the team much farther than was actually necessary.

– After Seppala arrived at the roadhouse at Golovin, thus completing his leg of the serum run, he rested and then started out for a leisurely return home to Nome. On the return, the team picked up the scent of a reindeer on the trail, and both Togo and another dog broke free of their leads, and went running off after the deer. Seppala had to remain to restrain the rest of the team, and in doing so lost sight of Togo and the other dog. He continued on into Nome without them, worried that Togo, especially (whom he had a great fondness for, and a strong bond with), would be mistaken for a wolf and shot by a hunter or other local citizen, or that one or both of the dogs might get their feet caught in a fox trap, which apparently was a fairly common occurrence for sled dogs at the time. Some days later, however, the two dogs wandered back to Seppala’s kennels, and were happily reunited with their worried owner.

Above: Togo’s stuffed and mounted body, displayed at the

Iditarod Trail Headquarters Museum in Wasilla, Alaska. Note the poor

condition of the mount. This is due to previous ownership by the

Shelburne Museum of Shelburne, Vermont, where it was displayed out in

the open. There, people could approach it closely and touch it (exposing it

to body oils and moisture, and pulling the fur out of the dead

skin when they would touch and pet it). The museum had purchased it

from Yale University’s Peabody Museum of Natural History, which had

it on display prior to that time. (Togo’s skeleton is mounted separately,

and still in possession of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, where

it is occasionally displayed.) This is an older photo. Please see the

Monuments & Mounts article on this site for more recent pictures.

Born To Lead

As a puppy (the only one in his mother Dolly’s litter at the time, or perhaps the only survivor), Togo’s great future was not immediately apparent. He ran a bit small, and he had developed a painful disorder which caused his throat to swell. He spent his early days in the arms of Constance (Leonhard Seppala’s wife), who applied hot rags to his throat to ease the pain.

And yet, in spite of the disorder, Togo became a troublesome and mischievous pup. Whenever Seppala would be out in the kennel yards, harnessing up a team, Togo would dash around nipping at the dogs, frustrating and distracting them. One reporter once wrote that Togo was “showing all the signs of becoming a canine delinquent“.

When he reached six months of age, Seppala decided he’d had enough of the puppy’s mischief, and gave him away to a woman who was looking for a house pet. Togo, however, did not take to the domestic life of a pet, and even though the woman spoiled him, he because worse and worse. In a matter of weeks, Togo had escaped from the woman’s house by leaping through a windowpane and working his way meticulously back to Seppala’s kennels. Amazed, Sepp took him back, later saying of him that “a dog so devoted to his first friends deserved to be accepted“.

However, Togo had not ceased to be a problem. He continued to harrass Sepp’s teams whenever they hit the trail. Whenever Togo got free of the kennel, and met a returning team, he’d dart up to its leader and jump at him. Doing this almost cost him his life once (noted in the previous post), when he ran up to a team of trail-hardened malamutes and was mauled. Togo had him rushed by dogsled to his kennels for medical attention. However, this experience would actually help to make him a better racing dog, as one of the hardest things to teach an inexperienced lead dog is how to pass another team without getting distracted and possibly being lured into a fight (or starting one). Togo never pestered another team again, always giving an approaching team a wide berth. When he would “pass by” another team going in the same direction, he would dig in, pull on the harness, yelp and rush on ahead. Sepp said that “…like a lot of humans, Togo had learned the hard way“.

He was about eight months old when he finally got the chance to show his quality as a sled dog and a potential lead dog. Sepp had to rush out with a team to a mining camp outside of Nome. A prospector had hired Sepp to take him up to Dime Creek, where there was word of a new gold strike. It was 160 miles away. Sepp had tied Togo up, leaving instructions that he be kept secure for two days after his departure, because he didn’t want Togo chasing after the team and then harassing the dogs in the rush they were in. Togo hated being tied up, and the same night that Sepp left, Togo broke free from his tether and jumped the seven-foot-high fence of the kennel, but got one of his hind legs caught in the wire mesh at the top of the fence. Squealing and yelping, he caught the attention of a kennel assistant, who came out and cut the mesh to free him. Togo dropped to the ground, rolled over, and immediately set off after Sepp and the team.

Togo ran through the night, following Sepp’s trail all the way to the roadhouse at Solomon, and rested quietly outside for the remainder of the night. The next morning, Sepp noticed that his team was off to a rather quick start. He assumed they had caught the scent of a reindeer ahead on the trail. When he looked ahead, and saw a dog running loose far off ahead of them, he figured it out. It was Togo up to his usual mischief. He darted about at the team, nipping playfully at the leader’s ears, and then occasionally charging off after reindeer. When Sepp finally caught him, he felt he had no choice but to put him where he could keep an eye on him…back in one of the wheel positions directly in front of the sled. The moment he slipped the harness around Togo’s head and neck, the dog became serious and resolute. The tugline went taut and he focused on the trail. This amazed Sepp, who discerned that what Togo wanted all along was to be a member of Sepp’s team.

Throughout the day, Sepp kept moving Togo up the line until, at the end of the day, he was sharing the lead position with the lead dog (named “Russky”). Togo had logged seventy-five miles on his first day in harness, which was unheard of for an inexperienced young sled dog, especially a puppy. Seppala called him an “infant prodigy”. And later added that “I had found a natural-born leader, something I had tried for years to breed“.

Above: Leonhard Seppala with Togo, after the serum run. This

photo clearly demonstrates Togo’s small size (under-sized for a

more typical Siberian husky of the time period…as noted above).

Seppala himself was only 5’4″ tall.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE SIBERIAN HUSKY

Part One – Siberian Origins

Used with permission from Mr. Mick Brent – Dreamcatcher Siberian Huskies/The Siberian Husky Welfare Association (UK)

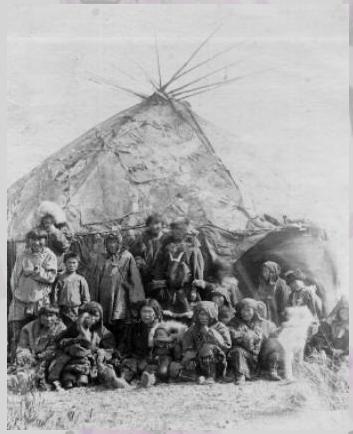

(Below – Siberian Sled dogs photographed circa 1901 by Vladimir Jochelson/Dina Brodskava during the Jessup North Pacific Expedition)

The dogs we now know as Siberian Huskies are an amazing example of selective breeding over time to produce a form which perfectly fits the function for which they were developed. Imagine the complex specifications if we tried to produce such a breed today:

We want a breed which will:

| 1 | Survive and function effectively at temperatures down to -50 degreesC without any artificial aids; |

| 2 | Pull a lightly laden sled tirelessly day after day over vast distances in arctic/sub-arctic conditions and enjoy it! |

| 3 | Survive and thrive on the bare minimum of food; |

| 4 | Be intelligent enough to take instructions from the sled driver, but also independently minded and analytical enough to be able to ignore such instructions if they are likely to lead the team into danger; |

| 5 | Survive and function comfortably at temperatures up to 35 degrees C |

| 6 | Be capable of hunting and catching its own food if necessary; |

| 7 | Be able to live happily with large numbers of other dogs with minimal friction; |

| 8 | Love people in general and children in particular so that they can be used in winter to sleep with the children and keep them warm; |

| 9 | Look absolutely beautiful at all times |

| 10 | Combine an infinite capacity and appetite for work with an ability to sleep anywhere and everywhere at the drop of a hat; |

| 11 | Be capable of jumping/climbing high fences |

| 12 | Be capable of digging holes and escape tunnels worthy of “The Great Escape” or “Colditz” |

| 13 | Be capable (if given the opportunity) of destroying almost anything in seconds; |

| 14 | Combine the characteristics of an iron-hard working sled dog with that of the softest lap dog. |

The Siberian Husky, which is directly descended from the sled dogs developed over a period of several thousands of years by the Chukchi people of North-East Siberia, fulfils all these “functions” within its beautiful and efficient “form.”

The Chukchi People, whose name was derived either from the Chukchi word “chukcha” meaning “rich in reindeer”, or the Russian “chavchu” meaning “reindeer people,” were primarily a reindeer-herding people living inland on the tundra with their reindeer herds. Like the Saami of Lapland, the nomadic herders used their reindeer products to make tools, clothing, dwellings and, of course, provide the basis of their diet and their transportation.

A smaller section of the Chukchi people – the “maritime: Chukchi – lived in summer coastal villages and hunted seal, walrus and whales for their food and used dog sleds for transportation. The landscape of Chutotka (the Chukchi land) is dominated by tundra interspersed with low mountains, with some areas of taiga in the south and west. The wildlife found in Chukotka includes Caribou (this is in addition to the domestic reindeer that are maintained in herds, wolves, bears (grizzly and polar), arctic fox, walrus, seal, whale, cranes and a variety of arctic birds. Summer temperatures can be very warm while the winters are (literally) arctic. Chukotka has the widest seasonal temperature variation of anywhere in the world.

The maritime Chukchi lived in summer villages of between 10 and 20 tents – twice the size of the reindeer herding Chukchi villages. These was considerable contact and trade between the two groupsand indeed, in some areas, both groups lived together and cultivated a lifestyle which included both reindeer herding and coastal hunting.

Their sled dogs were crucial to both the survival of the maritime Chukchi and the viability of their communities. Many of the characteristics still seen in today’s Siberian Husky have their origin in the Chukchi dogs going back several millennia. Their temperament, for example, had to be equable enough for them to coexist peacefully with both humans and other dogs. They could work amicably as part of teams of 20 or more dogs and their temperament was a crucial survival factor – out on the ice in freezing arctic temperatures, a major dog fight could mean tragedy if injured dogs meant that the team and the family froze to death. The Chukchi dogs were also sweet tempered enough to sleep with the children as “doggy duvets.” Night time temperatures were measured by the number of dogs necessary to keep the kids warm – eg three dog night, four dog night etc.

The economic and social importance of the Chukchi’s dogs was also reflected in their place in the Chukchi religion and mythology. A Chukchi legend held that two sled dogs guarded the gates of heaven where they had the power to reject anyone who had been cruel to dogs during their time on earth. Another legend claimed that during a time of famine, both human and dog populations were at risk of being wiped out by hunger. Only two baby puppies still remained alive, but with their mother dead, they had little chance of survival. A Chukchi woman suckled the pups at her breast so ensuring the survival of the breed and the co-dependent nature of the human-dog relationship. Ironically, this situation was to be replicated in reality during the 1860’s when the breed’s survival was again threatened by famine. This time the Chukchi’s sled dogs survived by judicious outcrossing to other local breeds (see below).

The conventional wisdom concerning the origins of the breed, claims that the Chukchi dogs were direct descendants in an unbroken line of pure breeding dating back some 1000, 2000 or 3000 years (depending upon which book/article/website you choose to believe). The reality is somewhat more complex and interesting. Many of the indigenous Siberian peoples have used sled dogs as transportation and have done so for thousands of years. Indeed, the 3000 year benchmark so often used in discussion of Siberian husky history may itself be a serious underestimate. The distinguished Russian archeological researcher N.N.Dikov, found evidence of Laika-type dogs in burials in the Kamchatka peninsular dating back 10,000 years.

(Dog Sledding Way of Life in Kamchatka – B.I. Shiroky – P.A.D.S. Newsletter #5)

In fact, the Siberian Husky and the Alaskan Malamute (along with 12 other breeds) have been identified as amongst 14 “ancient breeds” of domesticated dog whose genetic\lines have been distinct from the wolf for many thousands of years. Interestingly this research shows that the recurrent myth about northern peoples’ interbreeding of dogs and wolves is just that – a myth with no historical or genetic truth to it at all.

(“Genetic Structure of the Purebred Domestic Dog” – Science, Vol 304, May 21st 2004)

It may be that the Koryaks, the Iukagirs, the Chukchi, the Kamchadals and the many other paleo-Siberian peoples, at some time in their history were so geographically, culturally and economically isolated from each other tha

“..a long interchange between the peoples of Siberia and the natives of Alaska did exist from ancient into modern times.”

(John Douglas Tanner Jr. – Alaskan trails, Siberian Dogs pp15)

It is very likely that some interbreeding of their dogs may well have been the occasional result of such interaction. Indeeed, an archeological excavation of ancient Ipuitak sites at Point Hope in Alaska in the 1940’s recovered dog remains some 2000 years old, which were positively identified by scientists as those of Siberian dogs,\not local Alaskan breeds.

(John Douglas Tanner Jr. – Alaskan trails, Siberian Dogs pp15)

Further evidence of such possible interbreeding over the millennia can be seen from the fact that the research into “ancient breeds” referred to above, also found that genetically, the Alaskan Malamute and the Siberian Husky were very closely related.:

“In addition, the Alaskan Malamute is shown to be very closely related to the Siberian Husky, and its place of origin is far western Alaska, across the Bering Strait from the homeland of the Siberian Husky’s ancestors.”

(http://www.workingdogweb.com/RSH-2004-2.htm – “New breakthrough in dog genetics”

Much more recently (as mentioned above) a devastating series of famines suffered by the Chukchi people during the 1860’s, resulted in the death of the vast majority of their dogs. Many died of starvation and some were killed and eaten by desperate Chukchi to feed their families.

(Thompson & Foley – The Siberian Husky)

After this devastation, the Chukchi gradually re-established their sled dog stock by breeding their few remaining dogs with other available breeds including\primarily the smaller, red, foxlike Tungus Spitz.

(Thompson & Foley – The Siberian Husky)

Both the dogs above – the shaggier ‘wolflike’ one and the smaller, flatter coated ‘foxlike’ one (photographed in 1904) are Chukchi dogs.

From the middle of the 17th Century, increasing exposure to Russian influence – culturally, politically and economically – began to change aspects of Chukchi life:

“Ethnic Russians first encountered the Chukchi in 1642, when the Cossack Ivan Yerastov met them on the Alazeya river. In the 1640’s, the Russians built two forts on the Kamchatka, and commercial traders, fur trappers and hunters used these forts as a base and established permanent contact with the Chukchi. This contact brought many problems to the Chukchis. Diseases like influenza, mumps, smallpox and so forth spread amongst the population, and alcoholism became a problem as Russian traders often paid with vodka.”

(The Centre for Russian Studies (NUPI) – http://www2.nupi.no/cgi-win//Russland/etnisk_b.exe?Chukchi

Throughout the second half of the 17th and most of the 18th Century, the peoples of Siberia (and particularly the Chukchi – who were known as “the Apache of the north!” because of their fierce resistance to invasion) came under increased military, commercial and cultural pressure from Czarist Russia. The crack Czarist Cossack troops pursued a policy of genocide against the Chukchi, and in a series of skirmishes, the Chukchi with their dog sleds, managed to outrun them and avoid a final showdown. In 1649, Anadyr was established as a fortified outpost city for the Russian empirebut over the next 100 years or so it became a huge drain on Russian resources.For the period between 1710 and 1764, the maintenance of the fort at Anadyrsk had cost some 1,380,000 roubles, but the area had returned only 29,150 roubles in taxes. The Russians controlled the land, but not the people and it was costing them dear. The Cossacks were extraordinary warriors, but they did not understand either the terrain or the arctic conditions and suffered terrible losses (due to the inhospitable conditions – not the Chukchi). After a series of brutal military campaigns, Russia decided to try a different tack and tried to control Chukotchka through trade rather than violence. A treaty was made with the Chukchi giving them independence.

Unfortunately for the Chukchi, what defeated them in the end was firstly the consequences of opening Chukotchka to trade, and secondly the bureacratic”need” of the new communist rulers of Russia (after the 1917 Bolshevik revolution) to control and standardise everything in the name of “proletarian efficiency.” The new Soviet Union initially offered a free trade deal to the Chukchi. The inadvertent side effect of increased trade was the importation of a smallpox epidemic. The Chukchi people were decimated. Having inadvertently weakened the Chukchi with disease, the Soviets removed the velvet glove and deliberately executed all the Chukchi village leaders (who also happened to be the most experienced and successful dog breeders). The Soviets then set up their own dog breeding programmes designed to create the perfect Peoples Sled Dog.

As if this level of bureacratic control-freakery was not enough, in 1952 the Soviets issued a statement denying that the Chukchi dog had ever existed as a distinct breed and that the “siberian husky” was a US created breed whose origins had nothing to do with Siberia. Amazingly enough, although the Soviet Union is now itself history, many contemporary Russian dog historians still hold to this ‘official’ view. To confirm this, simply browse the website of the Russian “Primitive Aboriginal Dogs” (PADS) organisation – the Siberian Husky is not amongst the aboriginal dogs they recognise.

“It would be appropriate to mention that the Americans have developed and breed sled dog named the Siberian Husky and the term Husky can be translated as ‘Laika.’ However, this breed, in our understanding, does not have any relationship to Siberian dogs as I understand them. The Siberian husky is a cultivated specialised breed, which American cynologists obtained by selective breeding our sled dogs imported from northeastern parts of Chukotka, The Kolyma River and Kamchatka.”

Our Northern Dogs – B.I.Shiroky – in PADS Newsletter #8

Although understandable in one sense – after all, the Siberian Husky may no longer be regarded as a primitive aboriginal breed, it does seem strange to deny its relationship to such dogs – after all, every single Siberian Husky in the world has ancestry going back to the handful of entire dogs/bitches imported into the US in the early part of the 20th Century.

“The entire Siberian Husky breed goes back to the same dozen dogs of the 1930’s: Kreevanka, Tosca, Tserko, Duke, Tanta of Alyeska, Sigrid III of Foxstand, Smokey of Seppala, Sepp III, Smoky, Dushka, Kabloona, Rollinsford Nina of Marilym. There are two or three others none of which would constitute more than one half of one percent of a dog’s pedigree today.”

J.Jeffrey Bragg – http://seppalasleddogs.com/seppala-breeding-5.htm

Unfortunately, as a result of Russian invasion, famine, disease and Soviet politics, the Chukchi dog, as a distinct breed of Siberian ‘Laika’ no longer exists in any meaningful numbers, if at all, in its native land. Having said that, sled dog enthusiasts in Kamchatka are working with the few remaining aboriginal dogs to re-establish the Kamchatka sled dog, and as part of that programme, initiated the Beringia sled dog race – the longest sled race in the world at nearly 2000 kilometers long.The race is run from a village in Kamchatka (eg Esso) through Palana in the Koryak region, to a village in the far north (eg Markovo). The Esso-Markovo route at 1980km is the longest sled dog route in the world and takes three weeks to complete.

The Beringia Race – from http://www.thearctic.is

Ironically, as the breed came under increasing threat to its very existence in its own homeland, it began to gain a foothols in a new continent only a few miles away across the Bering Straits. Sled dogs had been used in Alaska for millennia, just as in Siberia. The influx of thousands of people as a result of the Klindike Gold Rush had led to a massive increase in the need forsled dogs. Thousands of dogs (often totally unsuited to work in arctic/sub-arctic conditions) were brought north f4rom Canada and the US. Jack London’s “Call of the Wild” is a fictionalised tale of one such dog – ‘Buck,’ a St. Bernard cross.

The new population of Alaska, often with money in their pockets, needed R&R after their exertions in the gold fields. Gambling joints, saloons and brothels flourished, as did the new sport of sled dog racing. Probably started by drunken bar-room boasts abou t who had the better or faster teams, the sport of sled dog racing soon featured organised events. The Nome Kennel Club was formed and organised the biggest of the events – the All Alaska Sweepstakes Race. First run in April 1908, the race was soon to become an annual \event and the showcase for the extraordinary abilities of the “little Siberian rats.”

Husky Spirits in the Sky

They hear a voice from deep inside,

when those speak, they must abide.

They whisper tales of long ago,

when huskies thrived in ice and snow.

Lonely nights without much food,

they gladly gave their servitude.

Adventures waiting each new day,

man and dogs, with just a sleigh.

Traveling without any fears,

all across those great frontiers.

And when their time came to pass,

the rainbow bridge they did advance.

When pointing snouts to the sky,

there’re calling out to those on high.

They sing a song for those above,

brother spirits they are thinking of.

Someday they will join that pack,

and knowing they will not come back.

Today might be their very last,

living large before its past.

They howl their tales of life on earth,

how far they’ve come since birth.

That’s when you’ll hear that soulful cry,

to the husky spirits in the sky.

TJ

Rescue & Awareness

This post is geared more to the new husky owner, and it is important to be aware of some things for the good of both dog and family. Huskies are strong dogs, and with that also comes a strong will. Many people believe in rescuing huskies, and I have no problem with that at all… if you are aware of potential problems.

First of all, you have no idea how that husky was treated in his previous home. It’s quite possible, and even probable that he was mistreated. When people don’t understand something they eventually lose their cool and take it out on the source of the problem.

The rescue orginization may not be aware either. A dog put into a new environment will usually be reserved because they don’t understand the new place. This dog may act completely docile and fool everyone involved. The next thing to be aware of is that people lie. Neither you, or the rescue has anyway to prove the history given by the person giving up the dog.

People normally don’t give up a dog because its perfect. There is a reason they gave it up, and more than likely it is a behavior issue. Now some normal husky behaviors could be enough for a novice to give up. Things like constant exercise, digging holes, chewing and destroying furniture, and maybe even eating the cat.

And then there is the more extreme ones. Aggressive behavior that in fact can be very dangerous to a family. This behavior may not be shown until some particular trigger sets the dog off. This can be anything from food aggression to objects like a broom that was used to beat the dog.

I would also like to talk about how this aggressive behavior can be created without even a new owner knowing it. Now at the risk of being chastised I’m going to tell you just exactly what I believe.

First of all, huskies have a hierarchical pack structure (fact). This means that someone is at the top and someone is at the bottom. And the rest fall someplace in between. You can read all the Berkley papers that disagree you want, and you would be wrong to believe that load of crap.

Not only does the pack have a structure… the huskies, like us, have a desire to move up the chain. Not all, but most are driven to rule. You don’t have to have more than one dog to have a pack. Your family becomes a pack to a husky without much thought about it.

Now some people are stronger willed than others. Some are pacifist that believe everything can be reasoned and talked about until a solution is reached. That is fine if you are dealing with another human, but it’s not fine when dealing with a husky.

This is what can happen to a puppy. Huskies are known as being mouthy. That doesn’t mean talking, it means using their mouths as we would our fingers. Everything goes in a husky’s mouth. Puppies teeth, and they chew on things, fingers included.

What happens is the timid person lets them do this without a serious correction. The bite is annoying more than dangerous at this age. The problem is the dog will soon grow to the point where it can become dangerous if not corrected at that early age. It also empowers the husky to do as he pleases. You are slowly putting him in a position of power in your pack.

I’ve seen so many answers to this behavior that frankly, I don’t think have a prayer of working. Things like distract the dog with a toy, redirect them with positive training methods. So, what are you going to do? Spend 24 hours a day distracting this dog every time it wants to bite? Every time it wants something?

What you are doing is allowing the behavior to continue. The dog was distracted sure, but he didn’t learn that putting teeth on human skin is not allowed. All you are doing is avoiding the problem. When that dog is grown you will have a real problem on your hands. By that time it has actally become a dangerous problem.

You cannot reason with a dog like a person. They do not understand your words, and even if they did, they don’t have the brain power to reason out what is fair/unfair etc. like a human being does.

You don’t have to Alpha roll the dog, but you have to instill that this behavior is not allowed. You have to instill in them you make the rules. Instead of yanking your hand back you can push your finger forward to the back of the mouth/throat like if you were sticking your finger down your own throat to vomit.

The gag reflex works just the same for dogs. A few times of this, and they soon learn that fingers are not something to chew on. This does not harm the dog anymore than it harms you, if you do it to yourself.

A rolled-up newspaper slapped against your hand with a very loud, “NO!” works wonders for many instances of bad behavior. The point being is you have to do something. Reasoning and being passive only lets the dog know it is in control of you, not the other way around. You’ve become lower in rank and that is not a good place to be as that dog matures.

A word to the wise no matter what kind of dog you rescue. Take what they tell you about the dog with a grain of salt. All they can tell you is what the person who gave the dog up said.

Observe it closely for a long time and in all types of interactions, and don’t leave it unsupervised with a small child. You wouldn’t leave your child unsupervised with a homeless person you rescued, so why would you do it with an animal?

TJ

Happy Birthday Cooper!

On December 3, 2014 another husky soul arrived in this world. I wasn’t there for his first two months, but I imagine his birth was like all of those before him. In fact, I didn’t even know about him until one day at the vet when I enquired about any of the other clients having huskies.

I guess it was meant to be, because they did know of a litter and gave me the phone number. I called and asked all the questions I could. I went to see the pups because the family only lived 6 miles away from me. Then I went home and toiled with wondering if it was the right thing to do. Whether I really needed another pet.

With 3 cats and 2 dogs already in residence I was torn. The price seemed too high, but it really wasn’t out of line… but I didn’t know that. I made an offer, and waited a day. Eventually they came back with a counter offer, and I decided to take it.

I looked at all the pups and asked for the most outgoing one. They informed me “That One!” So, I picked up this big boy puppy and took him home. My wife named him Cooper, and it seemed like a good name for him.

I expected him to be just like any other dog I’ve had, and I treated him as such. I bet he was thinking about how much he was going to have to do, to teach me about his kind. But he didn’t falter with the work ahead of him. He began right away to teach me through all kinds of tricks of the trade. Stubbornness, subterfuge, teeth, and many other devious plans that only the Siberian People know.

That first year was a hard one on both of us. Mainly because I was ignorant about the ways of the husky. But he never gave up on me. This was his new home and life, and he wasn’t about to give up unless I did. That is the way of the Siberian they just don’t quit. We butted heads quit a few times, but I slowly learned more and more each day by observing him, and reading everything I could about them.

I had bred and trained German Shepherds but this little guy was nothing like them. At first I thought I’d picked a dud because he just didn’t seem to understand the heel command. He wanted to be out front and pull me down the road. No amount of commands or pulling him back would stop him.

He was also clumsy and would trip over his own feet on a walk. I seriously began to wonder if something was off in him. It turns out he just wasn’t used to those big legs of his. Today he is graceful and has a smooth lope that is poetry in motion. A gentle giant who grew into those legs and body.

We stuck together and walked miles and miles. I started learning about sled dogs, and husky history, and it slowly started to come together. Cooper and I met half-way, I started to accept him, and he began to accept me. We learned about each other’s faults, and also the good things that make a great partnership work.

Now today…three years later I can’t imagine what it would be like without him. He is a magnificent critter. Full of life, a worker on the bike, and a wonderful companion. I sometimes call him, “Big Silly.” Because he has a certain humor about him in the things he does. A gentle and very large dog for a husky. When he works he stays focused on the task at hand. But when at home he is like any other pet for the most part.

He has some behaviors that annoy me at times, but I’m sure I have some he doesn’t like as well. I understand him now, and that makes it okay. He really has changed my life in many ways. These days I’m so Intune with these Siberians that I even paint them.

I think about them all the time, and hope they are safe while I’m at work. I’m so wrapped up in these people that I’ve even invested time and money into more dogs. Seppala Siberians, the great working line from the master Leonhard Seppala himself. The future will bring more Seppalas into the world and I hope to have as many as I can.

As our breeding program grows I hope to turn more people on to these amazing dogs. Maybe when I retire in a few years we can do a few races, run some tours and let others find out how amazing it feels to be traveling down a trail being pulled by them.

It all started on this day 3 years ago with a little ball of fur named Cooper.

Thank You Cooper for everything you’ve taught me, and your never-ending zest for life. I hope we have many more years of adventures together!

TJ